Name Issue: Bonus Case Study!

- Lord Orsam

- Sep 12, 2023

- 4 min read

This is a good one; the best, one could say, being saved until last.

George Spence Clarke aka George Gregory

George Spence Clarke was born in April 1848 in Cheshire. He looks to have been born 'illegitimate' to Eliza Clarke. We find him in the 1851 census recorded as the grandson to Eliza's father:

Eliza Clarke subsequently married a railway police officer called Samuel Gregory in Northwich. In February 1864, at the age of 15, George entered into the employment of the London and North-Western Railway Co. at Holyhead, Wales. His stepfather was still alive at the time and, as we shall see, it would seem that he was registered by the London & North-Western Railway as George Gregory.

When, five years later, George came to marry Ann Owen, he did so in the name of George Spence Clarke (although the register records his name as 'Clark'). His children all bore the surname 'Clarke'. Just to give one example, his daughter Mary Ellen, born in 1874 was baptised as below:

George remained with the London & North-Western Railway for his entire career. After spells in Liverpool and Rhyl, he moved to Crewe where we find him recorded as a Railway Carriage Inspector in the 1881 census living with his wife and five children (all called Clarke):

By 1891 he had moved to Leamington and is in the census as below:

Tragedy struck in 1898 when his youngest daughter, Eliza Ann, was killed in a boating accident in Leamington. George, who was then the foreman of the carriage department of the London & North-Western Railway, gave evidence at the inquest on 6 August 1898, as reported in the Leamington Spa Courier on 13 August 1898:

Here's the thing though. A few weeks later, George gave evidence before a magistrate in Leamington in the case of William Butler, a carriage cleaner charged with stealing money from the London & North-Western Railway. When he gave evidence, as the foreman of the carriage department of that railway, he did so in the name of George Gregory. Hence, from the Leamington, Warwick and District Daily Circular of 30 August 1898:

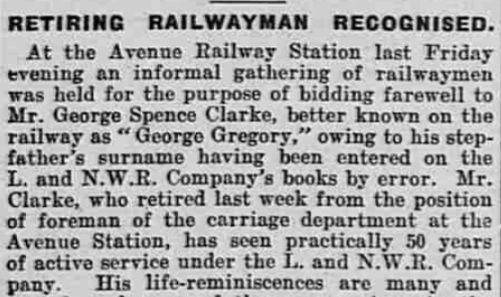

The explanation for why he did this can be found in the Leamington Spa Courier of 15 August 1913, following his retirement:

There we have it:

'Mr George Spence Clarke, better known on the railway as "George Gregory," owing to his stepfather's surname having been entered on the L. and N.W.R. Company's books by error.'

From this, it would seem that it was no simple matter for an employee to get their surname changed by their employer, once entered on the employer's books. Considering that he was recorded in error as 'George Gregory', one would have thought that this could have been easily corrected at some point during his nearly fifty years of employment, but it would appear not. On the contrary, he actually adopted the name on the railway and, as a result, must have been known to his colleagues as George Gregory,

What do we learn from this case?

Well at the most basic level it is yet another demonstration that a surname other than a birth surname is not a false surname, as has been claimed. Surely no one can argue that when he testified in the local police court under the name of 'George Gregory' he was giving a false name. We've seen that this is how he was known on the railway. He was, in other words, Foreman Gregory, not Foreman Clarke.

Equally, we don't see any indication in the press report of the criminal proceedings that George felt the need to inform the magistrate of his birth name. Why would he? What a waste of time that would have been. He wasn't obliged to do so. He wasn't giving a false name. He was giving the name he was known by to his employers which was George Gregory. He wasn't trying to hide anything. He was doing what made sense.

Now, I imagine one could say that, at the inquest, George testified under his birth name even though he also have said he was the foreman of the carriage department of the London & North-Western Railway but, of course, the inquest was in respect of the death of his daughter Eliza Ann Clarke so that it wouldn't have made sense for him to call himself George Gregory in this context. Further, there is no indication that he felt the need to inform the coroner that he was known on the railway as George Gregory. Why would he? He was there about the death of his daughter, not about any matter connected in any way with his employment.

We now have three men, Richard Bark, Robert Mandells and George Spence Clarke who were all known to their employers under the surname of their respective stepfathers even though they all married under the birth names. It confirms what I, and many others, have been saying for a long time which is that Charles Lechmere could also have been known as Charles Cross to his employers and work colleagues regardless of the surnames of his children (which is one point that has been made against this) and regardless of his surname on 'official' birth, marriage and death documents and on the census. It was perfectly possible.

Given that it was perfectly possible that Charles Lechmere was known as Charles Cross to his employer we have an entirely understandable and satisfactory reason why he might have thought it would be more sensible to testify at the inquest of Nichols under the name of Cross, just like he appears to have done at an earlier inquest while working as a Pickfords carman. We don't need to introduce other fanciful hypotheses nor do we need to think that, on the basis of him using his stepfather's surname, he was trying to hide anything or, above all, that he actually murdered Mary Ann Nichols.

LORD ORSAM 12 September 2023

An excellent and important find David adding further weight to your previous research. It couldn’t be clearer that there was just nothing at all suspicious about CAL using the name Cross at the inquest.